Rather than correcting faults after errors, if not illegality, are exposed, analysts all too frequently duck blame and justify fraud.

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is one example. In 2019, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation was urged to deny Prime Minister Narendra Modi the Global Goalkeeper Award due to “his government’s well-documented human rights abuses” by the official non-governmental organization of the Society of Friends [Quakers] and the 1947 Nobel Peace Prize winners.

Okay, so that’s fair enough, but why didn’t the AFSC ever offer an apology for its unwavering support of the Khmer Rouge, the ruthless government in Cambodia that killed over a million civilians?

As a kind of retaliation for disclosing a different development paradigm that rejects “exploitation by multinational corporations seeking raw materials, markets for surplus, and cheap labor,” the organization instead discounted “bloodbath stories”.

If the AFSC had thought about why it was so wrong in Cambodia, maybe it wouldn’t have embraced Hamas and North Korea to repeat its error. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are no better.

Both organizations worked together with the self-described human rights advocacy group AlKarama ten years ago. Human Rights Watch backed up its reports rather than admitting that its own inadequate vetting led to falsehood, and Amnesty International researcher Mansoureh Mills backed up while leveling false accusations at critics when it became clear that an Al Qaeda financier had founded Alkarama to weaponize false human rights accusations against Muslim Brotherhood opponents.

When former executive director Ken Roth unilaterally boosted the number of supposed victims in a study critical of the Sisi regime, he was upset that Egypt had refused to grant him a visa, which demonstrated how arbitrary the group’s methods was.

The group’s anti-Israel bias was so extreme that, in 2009, Robert Bernstein, the organization’s founder, bemoaned how the organization he had led for 20 years had gone completely insane in the pages of the New York Times. Its anti-Rwandan prejudice was so strong that, according to a 2017 report, the government of Rwanda had put some small-time offenders to death.

Human Rights Watch declined to provide an explanation for how an error of that magnitude could have gotten past its screening process when Rwanda later revealed that those people were not only living but also, in many circumstances, free.

The group was led into a moral abyss not only by political doctrine but also by greed. The director of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa division, Sarah Leah Whitson, allegedly proposed a trade-off at a 2009 fundraiser in Saudi Arabia: if Saudi businessmen gave money to Human Rights Watch, the organization would ease its stance on Saudi abuses.

The integrity and standing of human rights organizations are being threatened by pay-to-play and fraud more and more. Three types of persons were multiplied into millionaires during the course of the US’s two-decade endeavor to rebuild Afghanistan. Through corruption schemes, Afghan politicians amassed hundreds of millions of dollars.

Additionally, contractors benefited from projects that were rarely completed or survived. The easiest way for common Afghans to make millions, they informed me, was to set up a non-governmental organization that would speak humanitarian law and get funding from gullible American and European donors.

The US Congress convened a hearing last month to discuss Liberia’s proposal to establish a War and Economic Crimes Court to try those who committed atrocities or attempted to profit from the country’s two civil wars, which came to an end in 2003. Not the court per se, but some of the deception surrounding individuals who have attempted to benefit from pursuing Liberian war crimes, such as Civitas Maxima, a Swiss organization, and its local partner in Liberia, was at issue.

Following evidence that Civitas Maxima had instructed witnesses to give false testimony, courts throughout Europe have rejected proceedings against alleged war criminals and blood diamond dealers. It was more of an attempt to take advantage of the human rights sector than it was an individual shakedown.

The irony of human rights studies is that open countries such as Israel, Liberia, Morocco, and India are more receptive to criticism than closed civilizations such as Syria, Guinea, Algeria, or Pakistan. If Civitas Maxima and its allies were successful in getting a conviction, they may apply for large donations from organizations like the Center for Justice and Accountability, based in California, or other foundations.

The self-dealing worsens at this point. The same Center for Justice and Accountability that provided funding for the Liberia scam employed Beth Van Schaack as its acting executive director before she was named the US ambassador-at-large for global criminal justice.

Instead of taking responsibility for her own actions, she has aligned herself with Human Rights Watch to support the same organizations that are currently at the core of the issue involving witness manipulation.

Washington ignores the fact that Congress is calling for an inspector general probe into one of its top advocates for justice and human rights, while the US lectures India on human rights and purported international repression against Sikh terrorists who have been labeled as terrorists.

Numerous elements are involved in the human rights sector’s fixation on criticising India. Claims by human rights organizations that religious minorities in India are subjected to systematic persecution are refuted by thorough surveys conducted by reputable organizations such as Pew, which showed that religious minorities in India enjoy considerable religious freedom and experience minimal discrimination.

Nine out of ten say they feel “very free” to practice their faith, and many of them take ideas from one another in ways that would be confusing to Westerners. For example, over three-quarters of Indian Muslims believe in the Hindu concept of karma. Nearly one in five Jains and Sikhs celebrate Christmas, while a third of Indian Christians believe in the Ganges River’s purifying powers, according to Pew research.

Many organizations use selective information to malign India’s democracy. They omit to highlight the rules and accommodations related to religion that minorities are entitled to, including separate personal law, government subsidies for their own houses of worship, and a whole ministry dedicated to minority affairs that promotes and supports minority life and culture. Political activists who operate under the pretext of promoting human rights do not selectively choose; instead, they frequently misconstrue.

Take the Indian Citizenship Amendment Act, for instance, which provided fast-track naturalization for Sikhs, Hindus, Parsis, Buddhists, Jains, and Christians who escaped to India from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan prior to 2015. Human rights advocates said the law discriminated against Muslims, but they fail to mention that its purpose was to provide minorities in other states with a place to live. Their reasoning seemed strange.

The United States would not give preference to Han Chinese if it wished to save Uyghur Muslims against an unparalleled Chinese assault. Furthermore, the Lautenberg-Specter Amendment, which supported the needs of Soviet Jews facing discrimination and persecution from the government and allowed family reunification for individuals who fled Soviet tyranny, was not much different from the Citizenship Amendment Act.

Human rights organizations also misconstrued Kashmir’s Article 370 abrogation by India. In addition to giving Kashmiris greater legal equality, the abrogation ended the influence of dishonest intermediaries and feudal lords who hindered local farmers’ ability to sell their produce.

There may be serious issues with the US State Department, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch’s subjectivity and hypocrisy. Pakistan still maintains police state authority over the part of Kashmir it occupies, even though Indian Kashmir is currently thriving. The ongoing disgrace of Pakistan selling off Gilgit’s wealth and uprooting its people is all too frequently ignored. Minorities do indeed prosper in India, but in Bangladesh and Pakistan, they are persecuted on a systematic basis. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International may both denounce rapes and killings when they make news throughout the world, but they generally ignore the overtly discriminatory laws in both countries.

There may be serious issues with the US State Department, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch’s subjectivity and hypocrisy. Pakistan still maintains police state authority over the part of Kashmir it occupies, even though Indian Kashmir is currently thriving. The ongoing disgrace of Pakistan selling off Gilgit’s wealth and uprooting its people is all too frequently ignored. Minorities do indeed prosper in India, but in Bangladesh and Pakistan, they are persecuted on a systematic basis. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International may both denounce rapes and killings when they make news throughout the world, but they generally ignore the overtly discriminatory laws in both countries.

For instance, despite hundreds of kidnappings, forced conversions, and forced marriages of Hindu girls annually, there was not a single mention of a human rights violation against Pakistan’s Hindu minority in the most recent Human Rights Watch report on the country.

Also Read: PM Modi’s Russia visit strong foreign policy statement by India

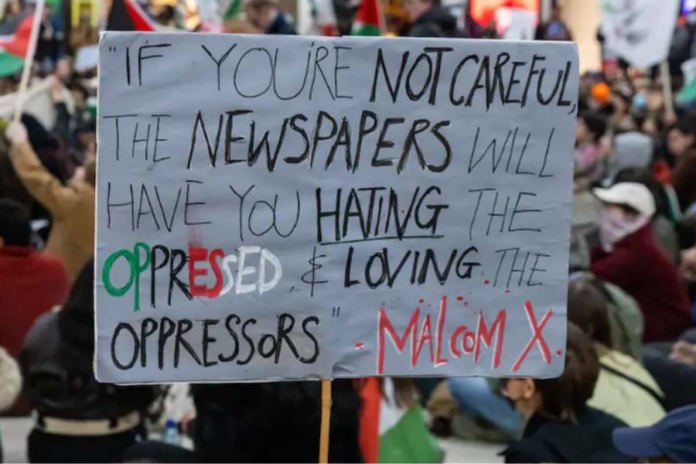

Human rights organizations advocate, yet their findings are meaningless because for many years they have placed politics above objective and ideology above technique. An obsession with India does not stem from the breach of humanitarian law by the Indian government; rather, it stems from the accusers’ dislike of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s electoral triumph, their hatred of Hinduism, and India’s relative openness and accessibility to its neighbors.

Furthermore, attacking India pays well and gives resident scholars the opportunity to live locally like colonial officers or advance their careers like Van Schaack. In any case, India would be justified to reject any report as political diatribe rather than an honest evaluation until human rights organizations hold themselves to professional standards and individuals with conflicts of interest, such as Van Schaack, recuse themselves or resign.